The Many Crises of the Stuart Century: Crisis 2, Plots and Conspiracies

This is the second in a series of posts on crises in the Stuart period that have contemporary resonance, based on the book A Monarchy Transformed, Britain 1603-1714 by Mark Kishlansky

Charles II's reign is usually remembered for licentiousness, disease, and corruption, as well as for the Great Fire. But it was torn by two major conspiracy scares, the Popish Plot (1678-1681) and the Rye House Plot (1683), where many people were arrested, tried, and imprisoned, exiled, or executed.

The Popish Plot

They called him "Titus the Liar"...long after it didn't really matter

Exactly what actually planned by anyone and who was actually guilty of anything is completely unclear. The Popish Plot was started by a genuinely odious mountebank and opportunist named Titus Oates, 29 and newly returned from abroad, where he had been rejected by several Jesuit schools. Oates seems to have been a brilliant confabulator. He had an almost supernatural talent for discerning what someone wanted to hear, a seemingly total recall of the details of every lie he told, and an ability to rapidly incorporate new events into his growing story. He was helped out by the fact that, if you accuse enough people, one of them will have done something suspicious that can be worked into the story.

Everyone was terrified of Catholics, the enemy within, and the knowledge that the childless King's heir was his younger brother James, who had become Catholic, put everyone on edge. Charles was not theologically reliable himself—and both brothers were in the pay of Louis XIV (though seldom providing value for money, pretty much the story of the Stuart dynasty as a whole). When the man to whom Oates had gone twice to swear evidence, Edmund Berry Godfrey, was found face down in a ditch on Primrose Hill, seemingly murdered, a crime that has excited a lot of speculation from that day to this, it seemed to be evidence that Oates was telling the truth.

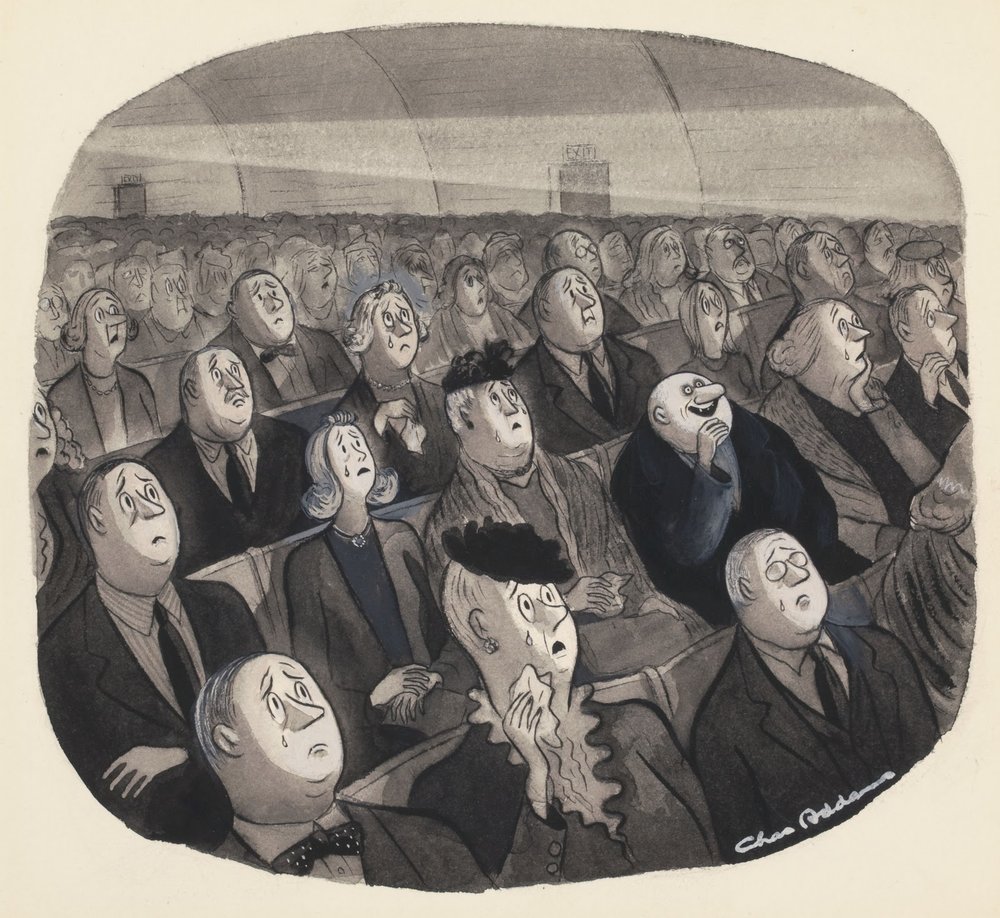

At least 15 people were executed, accompanied by mass demonstrations. Other informers, seeing a good opportunity, jumped aboard the conspiracy, informing on their neighbors, who were arrested in their turn. It became a crime to even deny the existence of the plot. Informers, mobs rampaging through the streets, the terror of arbitrary arrest: various people used the panic for their own purposes, but this was not any kind of top-down state terror. In fact, King Charles was really in part the target, and his attempt to have Oates arrested was unsuccessful. This was a genuine mass movement started by one failed seminary student, who struck a match amid a huge stack of dried kindling.

The frenzy went on for nearly three years. Oates was eventually disgraced, rejected by many of his former allies, who now found him inconvenient.

The Rye House Plot

In 1683 Charles found a pretext to strike back at his enemies. There was a plot to murder both him and James simultaneously, as they were returning from a horse race in Newmarket. Though there were definitely several groups who were plotting rebellion against the Stuart monarchy, no one has ever known how well-organized this particular operation was. It served as an excellent opportunity for Charles to get his own back, harking back to the grandaddy of all anti-Stuart plots, The Gunpowder Plot, and use the fear of conspiracies to move against his enemies, which included much of the population of London. This frenzy was directed at Dissenters, those Protestants who were not part of the state Anglican church, including many Quakers. Again, many arrests and executions. This time the operations really were top down, directed by Charles himself.

It doesn't take social media to get rumors, fake news, mobs, violence, and intergroup strife. But it's definitely worth taking a look at the reign of Charles II to get a good sense of how various forces can try to take advantage of inchoate rage and panic to achieve their own ends. I'd like to think we were beyond mass arrests, perjured evidence, and panicky magistrates trying to calm down the mob before it turns on them, but sometimes I am not so sure.

What kind of Plot do you think would be most suitable for our own touchy era?

And will the first one be against our monarch, or be run by him?