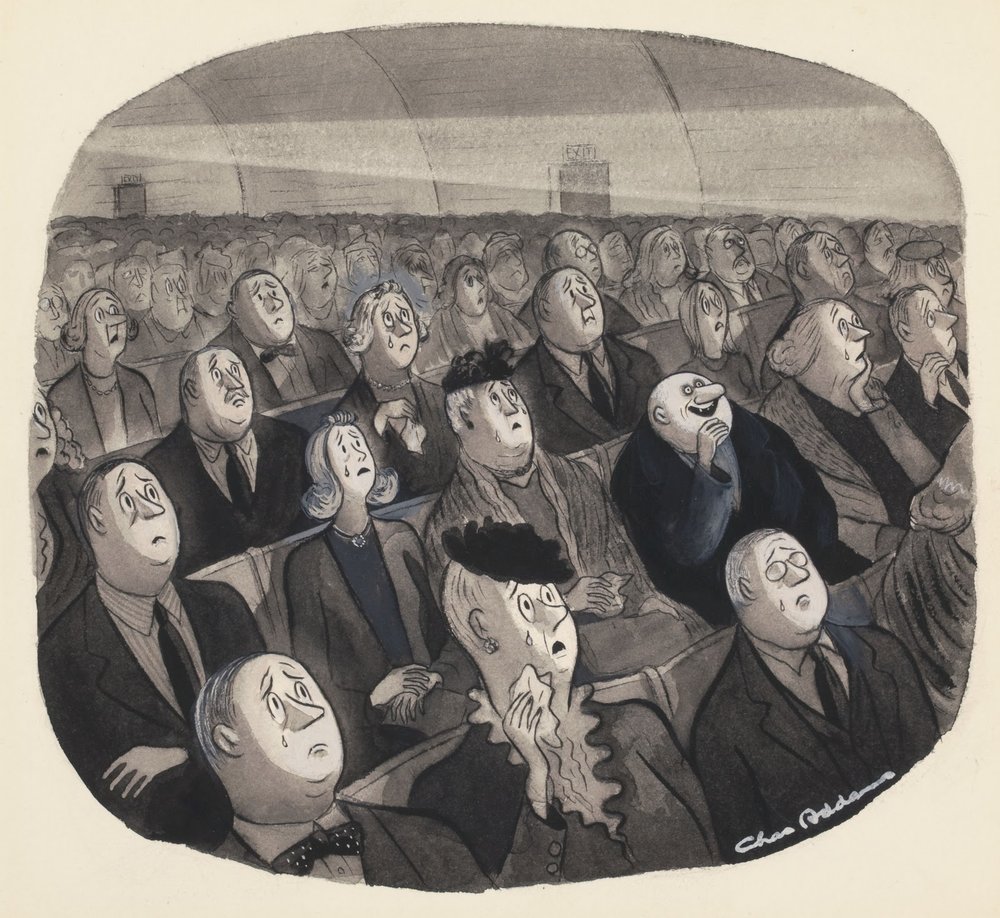

Miss E and I both loved it. So, really, a good date movie. Men, if you're looking for battlefield scenes, this is no Barry Lyndon—incidentally, the first movie where interiors were filmed solely by candlelight, a style shown to great effect in The Favourite. But watching three brilliantly acted sparring women, any of whom could eat you alive, definitely has its charms. The psychic violence is right near the surface. And all the sex is, in some way, also about power and manipulation (once, um, literally). What more could you ask for?

As always, your dating mileage may vary, and I make no guarantees.

Plus, it has some brilliant set pieces, like the absurd dance sequence that shows Queen Anne that she is physically increasingly unable to enjoy anything about life even as it makes everyone else seem like some kind of Olympic athlete. This clip is annotated with what they called the various moves during shooting.

Is historical fiction more like history or like fantasy?

I'm sometimes curious about the place of historical fiction in a world where history is so little known, even among the educated classes. In some ways, The Favourite could have been set in any court, since the roiling world outside the palace where modern science and literature were in the process of being invented never plays much of a role. But the characters were real and interesting, and misbehaving English-speaking royals are always of interest.

Movies set in this era (I'm thinking particularly of The Draughtsman's Contract, an acknowledged influence on director Yorgos Lanthimos) always love the huge wigs, the foppish dress, and the ludicrous and childish misbehavior on the part of aristocrats, in this case duck racing and pelting laughing fat men with fruit. Silent slo mo always helps make these activities seem more compelling than they could possibly have been.

The costumes are inspired by historical ones but have a a modern feel to them. The endless hallways and chambers of the palace have an almost Gormenghast feel to them. A character is poisoned and then imprisoned in a dismal whorehouse (a movie like this could scarcely show any other kind), which is actually the only other interior location shown.

I'm not a huge fan of much historical fantasy fiction, but if more if it was like this, I might change my mind. I'm willing to be enlightened if anyone has any suggestions for me.

How women could exert power

Historically, ambitious women who sought to influence events lacked access to the violence and coercion that lie underneath the exercise of power, and so were forced to rely on emotional manipulation and sex. Men, who did have violence at their disposal, always found this contemptible, even as they found themselves responding.

Sarah Churchill, played with self-confident aplomb by Rachel Weisz, is an actual player in politics, helping manage the finances of the War of the Spanish Succession on behalf of her husband, the Duke of Marlborough, and via her access to Queen Anne. Marlborough keeps winning increasingly bloody and expensive battles, but battlefield defeats are not enough to force France to sue for peace. Parliament is growing restive, facing tax increases to finance an increasingly expensive, stalemated war.

Abigail Masham, introduced into the palace by her relative Sarah, is destitute, without any power at all. She manages to gain Anne's trust and affection, makes a favorable if loveless marriage, and gains power in the palace.

The result is a power struggle for emotional control of the sad, ill, sometimes befuddled, sometimes surprisingly shrewd Anne, who is less easily controlled than either would-be puppetmaster thinks.

The movie gets the hothouse court atmosphere down, though with perhaps a bit more fisheye lens action than necessary. This is the era when once-powerful French nobles struggled for the privilege of collecting Louis XIV's chamberpot. Tiny privileges loom larger than military victories, long emotional sieges can lead to sudden changes in status, and taking your eye off the ball for any length of time can lead to personal disaster. It would be nice to achieve power and wealth some other way, but this is pretty much the only game in town.

A one point late in their conflict, Sarah Churchill realizes something about her rival, Abigail Masham: "We're playing different games". And it's true. At story start Abigail has nothing but a connection to her more powerful cousin. She is scrabbling desperately for survival. Sarah is playing the larger game of state and international politics. In the end Abigail achieves...well, you should see the movie to see what she achieves. It's a brilliant vision of balancing what you want versus what you're willing to give up.

The game is hard fought, and the outcome is in doubt until the very end. And maybe past it. I was actually startled by how much I enjoyed it.

What genre do you think The Favourite is?

I think of it as historical fantasy without the tedious magic. You can pour horror, suspense, and political intrigue into that bucket without missing a drop.